The Late-War Bomber

By WavesToJets

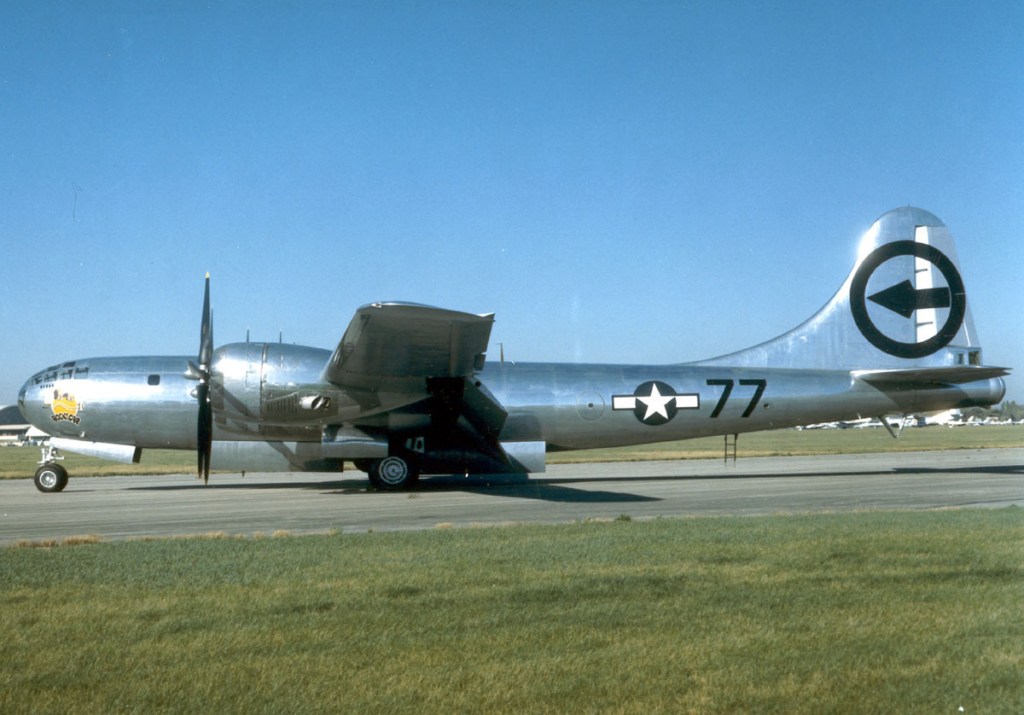

The B-29 Superfortress was a World War II-era heavy bomber manufactured by Boeing. Characterized by four large radial engines, a long vertical tail fin, and a hemispheric, multi-windowed step-less cockpit, the Superfortress was used almost exclusively in the Pacific Theater of World War II .

The B-29 was also used extensively as a bomber in the Korean War, as well as in reconnaissance and air-to-air refueling missions throughout the 1950s and early 1960s.

The B-29 was a massive airplane, with a length of 99 feet, a wingspan of 141.25 feet, and an empty weight of 74,500 pounds. It was capable of carrying 5,000 to 20,000-pound bombs.

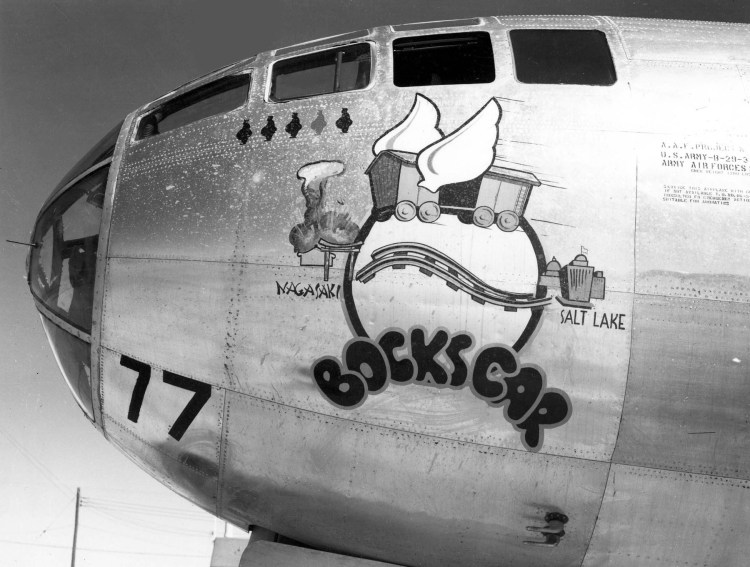

The Enola Gay and Bockscar were both B-29s; these planes carried and delivered the first atomic bombs used in combat against the Japanese on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

Technological Background

The B-29 was borne out of the United States Army Air Corps’ (USAAC) need for a fast, long-range heavy bomber. Specifications were drafted in the late 1930s and early 1940s for such a craft to eventually replace the USAAC’s main heavy bomber at the time, the B-17 Flying Fortress.

In February 1940, the USAAC specified they wanted a craft that could travel 5,000 miles, could carry a maximum bomb load of 2,000 pounds, and have a speed of 400 miles per hour.

Lockheed, Consolidated, Boeing, and Douglas all submitted design proposals, but Boeing ultimately secured two contracts – one for two flyable prototypes, and another for 250 of Boeing’s bombers (and some spare bomber parts) – in September 1940 and April 1941, respectively.

Boeing was not alone, as Consolidated’s bomber design would become the B-32 Dominator. Though the Dominator saw combat in its own right, it was originally intended to serve as a back-up for the B-29.

Boeing’s B-29, however, took precedence as the USAAC’s (renamed the US Army Air Forces [USAAF] in 1943) main high-altitude heavy bomber, especially in the Pacific.

Boeing’s development produced a four Wright R-3350-23 Duplex Cyclone-engined, 99-foot long, 74,500-pound bomber with a wingspan of 141 feet, 3 inches. It also had three pressurized cabins to compensate for high-altitude conditions.

Each engine was a 2,200 horsepower turbo-supercharged radial engine powering 16-foot, 7-inch four-bladed propellers.

These engines could bring the plane up to 30,000 feet without hindering speed performance – a boon for high-altitude bombing runs.

The plane would also have a range of a little over 3,200 miles, which suited the long-distance style of war in Asia and the Pacific.

Innovations in gun turret technology distinguished the B-29 from other heavy bombers. The plane was designed to have five gun turrets – two on top (one in the forward position, one towards the rear), two on the bottom (one in the forward position, the other in the rear) and one tail gun turret.

These turrets were controlled remotely by a gunner crew and were operated with electronic analog computers – which used fluid variations in wind and atmospheric conditions to calculate the approximate location of enemy planes. The plane’s altitude, speed, and air temperature all gave the computers enough information to change the “leading” aim position of the guns.

The gun turrets also could be controlled manually (though still remotely, the gunners were in the cabin, not near the turrets) should the computers be inactive.

Gunners could control more than one turret at a time. Turret use was spread between left gunner, a right gunner, a tail gunner, and a fire-control officer – who could delegate turret control among the other gunners as necessary.

Each of the gun turrets had two .50-caliber Browning machine guns, with the exception of the tail gun turret, which also had a 20-millimeter cannon. In later versions of the B-29, the 20-millimeter cannon was removed. In some cases, all guns were removed to reduce the plane’s weight and increase speed.

Postwar, the B-29 would be fitted with 3,500 horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-4360-35 Wasp Major engines. These versions were known as the B-29D, and later as the B-50.

The B-29 had a lengthy and troubled test period. Though designed around 1940, the finished B-29 would not arrive in the India for USAAF use until April 1944.

There were also different accidents in testing the plane, for example, a severe engine fire and crash of a B-29 prototype at Boeing Field in Seattle on February 18th, 1943, killed over 30 people. However, the B-29 came to be a technologically innovative, high-altitude, powerful bomber whose role in the latter part of World War II was undeniable.

In Service

Use of the B-29 in the North African and European theaters was discussed among the USAAF, but it was ultimately determined that the plane would be used in Asia and the Pacific.

The B-29’s first combat use would be in the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater, with planes arriving in India in April 1944.

The planes would be used against Japanese targets in China, Manchuria, Southeast Asia, and mainland Japan in a strategy called “Operation Matterhorn”. The B-29s would be based in India and Chengdu, China, and would make the high-altitude, long-distance trips needed to bomb their targets.

The bombers were first used in combat on June 5th 1944, against the Japanese Makasan rail facility in Bangkok, Thailand. This mission launched from bases in eastern India, a round trip of over two thousand miles.

Out of ninety-eight B-29’s, fourteen had to abort the mission due to engine failure, five crash-landed upon return, and forty-two were diverted to other bases because of low fuel. Though only eighteen bombs hit their intended target, the mission was somewhat successful as no planes were lost to enemy fire.

Over June 14th and 15th, 1944, a total of sixty-eight B-29s successfully set out from Chengdu, China to attack Japanese metal works factories in Yawata on the island of Kyushu, Japan.

This group was originally part of a larger group of ninety-two B-29s loaded with bombs in India, flying over “the Hump”, and landing in China for refueling. Many of these planes did not make the initial trip over the Himalayas and had to return to the Indian bases – and one crashed on the way to China.

Seventy-nine B-29s made it to China to refuel, and some were held back from the main mission. Even more planes were kept away from the main mission because of mechanical failure and a crash en route to Japan.

Out of the sixty-eight B-29s that left Chengdu, only forty-seven managed to attack the intended target – with only one 500-pound bomb actually on target.

Still, the other B-29’s that actually made it to Japan managed to hit secondary targets and viable targets that presented themselves by chance. One plane was lost to enemy action, and others to crashes of other reasons (likely mechanical).

A night raid performed by B-29s attacking separately, the mission against Yawata was not a strategic success. But it was the first major raid on the Japanese home islands since the Doolittle Raid of 1942 (in which B-25 Mitchells were used), and a highly-publicized morale-booster for the Americans.

More B-29 raids out of India and China would reach Japanese positions in China, Southeast Asia, Manchuria, and on Formosa (Taiwan).

An incendiary attack intended for Japanese factories and shipping in Hankow (Wuhan), China on December 18th, 1944 started a firestorm that destroyed the city. The attack claimed at least 20,000 civilian lives. As General Curtis LeMay was in charge of the XX Bomber Command at the time, the attack would serve as his inspiration for the firebombing of Tokyo months later, under his orders.

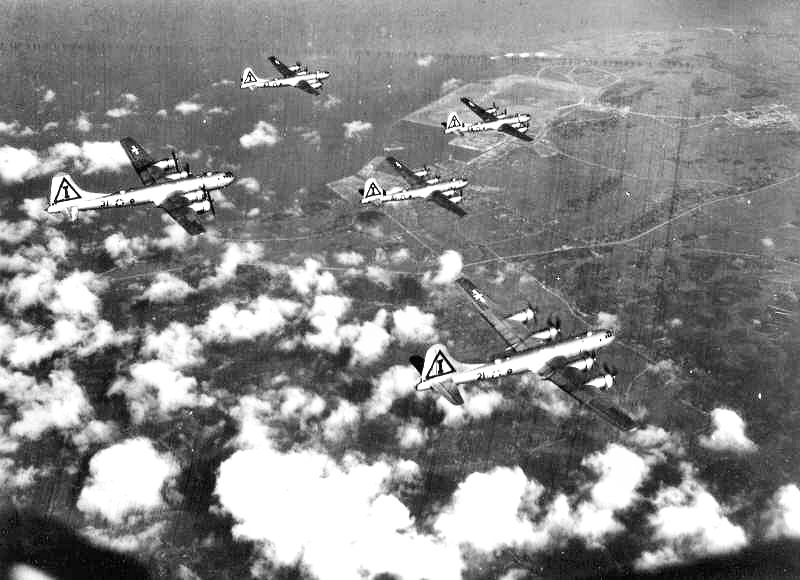

B-29s operating out of Chengdu bases would prove to be difficult to supply logistically, as well as vulnerable to Japanese attacks. By December 1944, B-29 attack operations were determined to be based out of the island of Tinian in the northern Marianas Islands (as well as Guam and Saipan).

These western-Pacific locations would be easier for ships to provide supplies, and, as remote islands, almost invulnerable to enemy attack.

It was from the Marianas that B-29s would be launched to attack Japan in 1945 – notably on attacks on Kobe, Nagoya, Osaka, and Tokyo. The firebombing of Tokyo on the night of March 9th – 10th, 1945 was one of the most, if not the most destructive air attack of the entire war.

Low altitude B-29s (279 in total over their target) dropped incendiary weapons over Tokyo, destroying over 267,000 buildings and killing over 83,000 people, including civilians. Though the attack was militarily successful, its morality – especially in terms of its civilian death toll – has since been debated.

The same could be said of the later atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Specially-constructed B-29 units (named “Silverplate” B-29s) were manufactured in order to deliver atomic bombs, including the Enola Gay (the B-29 that carried the uranium bomb “Little Boy”, dropped on Hiroshima) and the Bockscar (that carried the plutonium bomb “Fat Man”, dropped on Nagasaki).

These planes had pneumatic bomb bay doors, improved engines and propellers, and were stripped of excess armor and guns (only the tail gun turret on the Enola Gay, for example, was still equipped with two .50-caliber machine guns). These “Silverplate” bombers were also lighter, faster, and could carry a greater fuel load.

The 509th Composite Group – headed by Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr. and based on the Marianas island of Tinian – used 15 Silverplate B-29s in the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

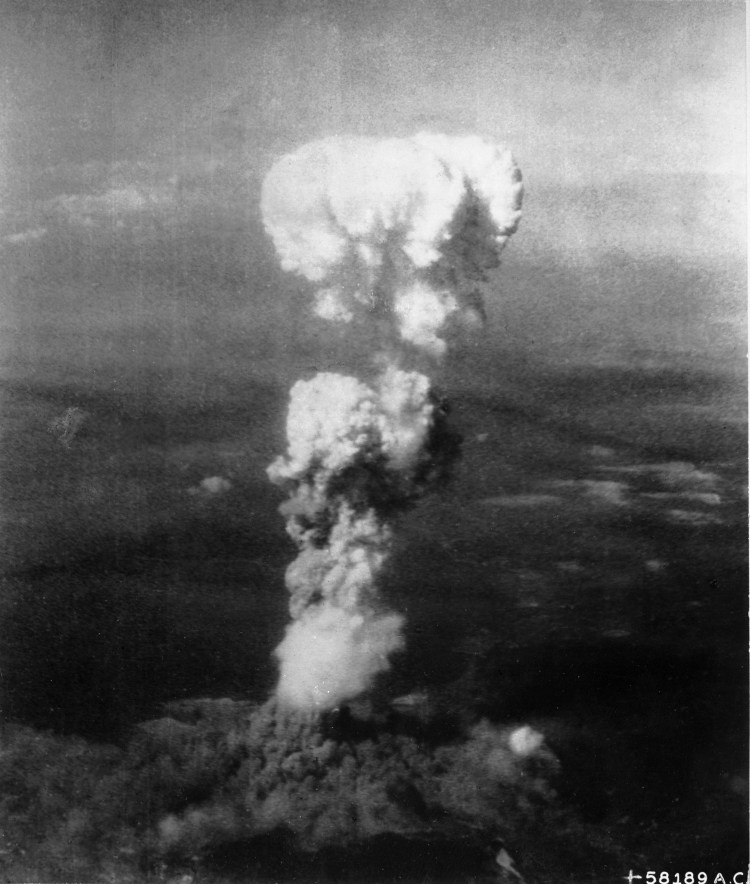

The Enola Gay (so named by Tibbets after his mother) dropped a 9,700-pound uranium bomb over Hiroshima, Japan on August 6th, 1945 at about 31,000 feet.

The bomb was detonated around 2,000 feet over the city, resulting in a massive explosion and the deaths of over 70,000 people in the initial blast. Hundreds of thousands of more people would die as a result of radiation sickness.

The Bockscar dropped a 10,300-pound plutonium bomb over Nagasaki three days later on August 9th, 1945. This bomb was detonated about 1,600 feet above the city and killed around 40,000 people in the initial blast.

Over 20,000 more people would die afterwards as a result of radiation sickness. This, and the Hiroshima bombing, prompted Japan’s surrender to the Allies six days later on August 15th.

Though Boeing would cease production of the B-29 in 1946, the plane would be used in the Korean War. B-29s dropped over 160,000 tons of bombs on enemy airbases, bridges, and supply lines – and shot down a total of 27 enemy aircraft.

A few B-29s were also loaned to the British and the Australians. In the UK, the plane was used for testing and disinformation campaigns (to lead the Germans to believe the plane would be used against them). In Australia, the plane was used for testing, mostly after World War II. In the Soviet Union, the Tupolev Tu-4 was a reverse-engineered plane derived from captured B-29s.

The B-29 Superfortress In Flight

The B-29 Superfortress was designed specifically for high-altitude bombing. As such, B-29 pilots could, and would, bomb target from altitudes of 30,000 or more feet. This left the planes nearly invulnerable to all but the largest of anti-aircraft guns and high-speed enemy fighters.

However, accuracy was limited at higher altitudes – and real-life experience in bombing runs on China and Southeast Asia proved this. Furthermore, high-altitude flights could strain the engines, causing frequent engine fires.

In order to make devastating blows on concentrated areas, USAAF General Curtis LeMay approved of bombing runs made at night at altitudes of 5,000 to 7,000 feet.

Such was the case during Operation Meetinghouse, the incendiary air attack on Tokyo on the night of March 9th, 1945. A total of 1,665 tons of incendiaries were dropped on the city; the attack resulted in fires that covered 15.8 square miles. About 80,000 Japanese military and civilian lives were lost; as were 14 out of the 279 attacking B-29s that reached the target area.

Bomber crews were trained to avoid flak, or anti-aircraft fire. Pilots had to time the explosions of the leading shell bursts in accordance to their frequency and shift course as required. They also would make adjustments to avoid flak in accordance to their altitude.

The B-29’s flak analysis officer would calculate the range, concentration, and probabilities of anti-aircraft fire and rank the bomber’s different possible headings – based on the likeliness of encountering enemy flak – and relay this information to the rest of the crew.

Model Variations

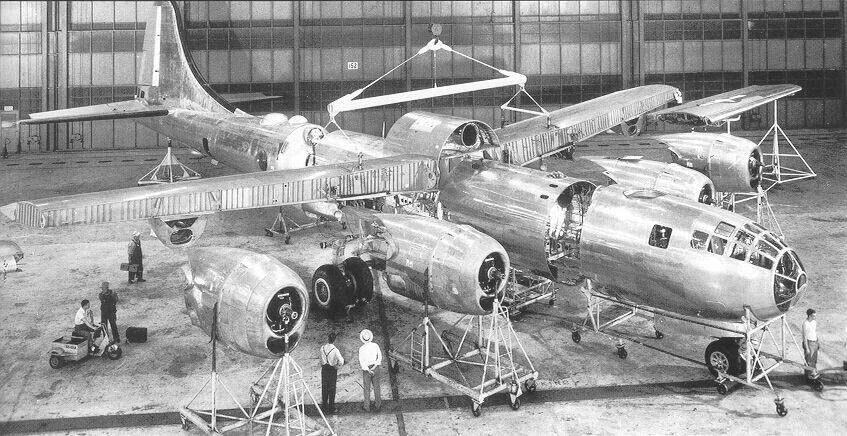

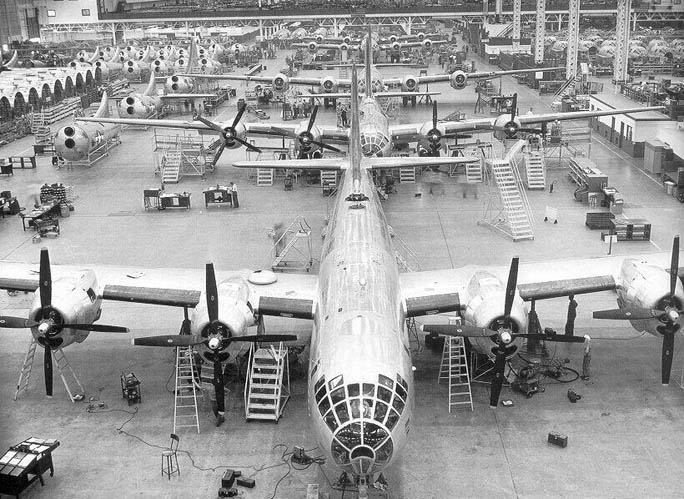

The B-29 was manufactured in several locations during the war. Among these were the Boeing factories of Renton, Washington and Wichita, Kansas, the Bell factory at Marietta, Georgia (as it was near Atlanta, it was referred to as “Bell-Atlanta”) and the Martin factory in Omaha, Nebraska.

The B-29 was made into several variants, including the:

B-29 – The first production version of the bomber; a little over 2,500 of these planes were built.

B-29A – A production version with a greater number of forward machine guns and a three-piece wing assembly. Over 1,100 of these were built.

B-29B – A version made for high-speed, low-altitude flights. Almost all defensive gun turrets were removed (except for the tail). Over 300 of these were built.

B-29D – A variant that incorporated 3,500-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-4360-35 Wasp Major Engines. Renamed the B-50A Superfortress, used after World War II. 79 produced.

The Silverplate B-29 – A variant designed specifically to hold and deliver atomic bombs. 65 were produced, a further 80 B-29s were modified under the post-war “Saddletree” program.

A total of 3,690 B-29s were produced. Additional B-29s were modified for fire-control, jet, and cold-weather systems testings, usually one type of modification per plane.

Other B-29s were modified for photo reconnaissance, weather monitoring, sea rescue, in-air refueling testing, airborne early warning/radar, naval patrol, and experimental aircraft carrier purposes.