The Eagle

By WavesToJets

The McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle has come to be renown as, and perhaps synonymous with, an extremely capable modern jet fighter. Its capacity for air-to-air, and later, air-to-ground combat has led to numerous victories over decades of conflicts.

But there is much more to know about the F-15 Eagle — from its technical capabilities to its gravity-defying performance in-air, the F-15 has plenty of impressive qualities you may never have heard about. Here are five facts about the F-15 Eagle.

1. The F-15 was developed as an air-superiority fighter.

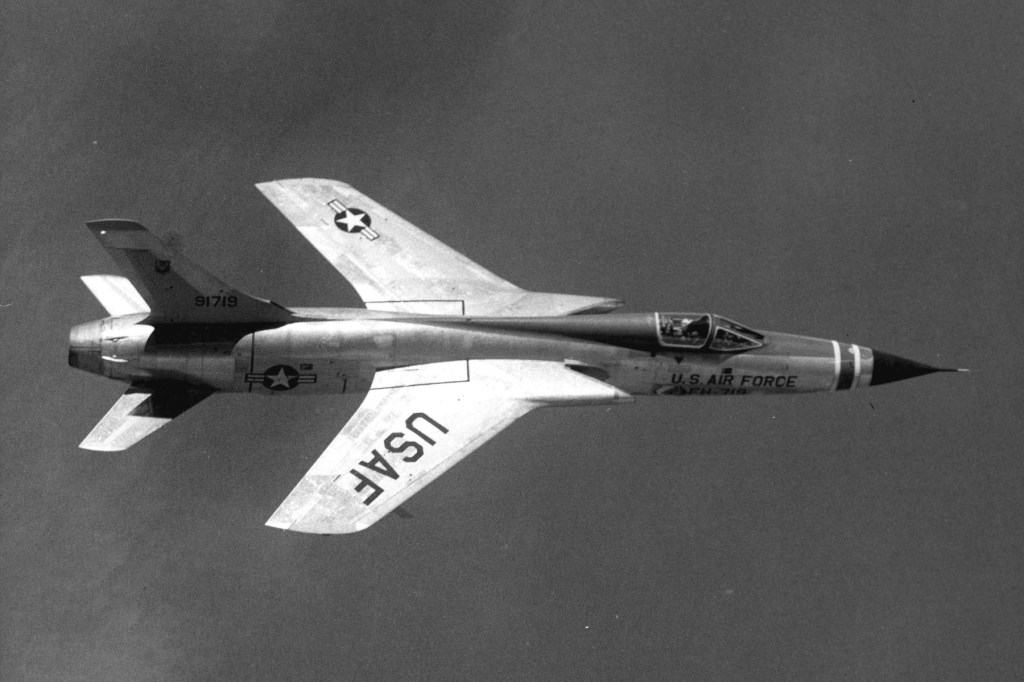

In the early to mid-1960s, jet fighters such as the U.S. Air Force’s (USAF) F-105 Thunderchief were large, fast, and heavy aircraft designed for multiple combat uses over long ranges.

These aircraft came to be equipped with such features as long-range radar, radar-guided missiles, and large arrays of conventional bombs. In the case of the F-105, this was at times in excess of 12,000 pounds.

Though these features would make the F-105 good for low-altitude bombing and ground attacks, it had its vulnerabilities. It was not as capable in air-to-air combat as it was attacking ground units, and needed escort for ground-attack missions.

When two F-105s were lost to MiG-17s (an outdated enemy aircraft model) over Vietnam on April 4th 1965, this underscored the need for more capable air-to-air fighters.

As far the remainder of the Vietnam conflict was concerned, the General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark and the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II served as the American military’s primary high-powered, high-speed, multi-purpose combat jets.

The F-4 could engage in air-to-air combat – whereas the F-111 was not designed to do so. Both, however, were capable of carrying heavy loads (18,000 to over 31,000 pounds) of ordinance – including (in the F-4’s case) long-range guided air-to-air missiles.

However, even the nature of these newer airplanes was argued by USAF and Pentagon-adjacent figures like Col. John Richard Boyd, Pierre Sprey, Charles Meyers Jr., and Thomas P. Christie (collectively, and informally, known as the “Fighter Mafia”) as being somewhat impractical in air-to-air combat situations.

Thus, Boyd and his contemporaries argued for the construction of somewhat smaller, lighter, more manueverable fighter jets with less emphasis on top speeds and long-range radar capablilites. These new fighters, they argued, would be able to handle subsonic air-to-air combat at a closer range, as well as be produced in greater numbers.

Roughly at the same time, the USAF and the U.S. Navy were at odds over what a jet fighter intended for both branches would look like. The USAF had been looking for a more manueverable aircraft, while the Navy looked for a more long-range aircraft capable of interception and defensive roles.

Robert McNamara (the then-U.S. Secretary of Defense) stated on February 14th, 1961 that both branches should work together to develop one aircraft to satisfy all of these combat needs. The resulting aircraft, the F-111 Aardvark, was a result of what was called the Tactical Fighter Experimental (TFX) Program.

As the 1960s progressed, however, branch-specific experimental programs continued. The USAF’s “F-X” program, for example, worked to develop an airplane to satisfy the USAF’s jet fighter combat needs.

The Navy, meanwhile, engaged in the “VFAX” program – which resulted in the development of their Grumman F-14 Tomcat. Both military branches, as it turns out, ended up making smaller, relatively lighter, more manueverable fighters in their respective programs.

By the late 1960s, the USAF’s “F-X” program was gearing to match (and surpass) the performance of the Soviet Union’s latest fighter, the MiG-25 – produced by Mikoyan-Gurevich – and unveiled in 1967.

The MiG-25 was a two-engined, wide-winged, high-flying jet interceptor that could reach a top speed of Mach 2.83. It could reach a service ceiling of 67,900 to 78,740 feet, and was composed of parts made of mainly of stainless steel, rather than aluminum.

The F-X – and the resulting F-15 – would not be able to fly nearly as fast or high, but this corresponded with the USAF’s design request. The USAF requested the F-X to have a higher thrust-to-weight ratio (1:1, as opposed to the Mig-25’s roughly 1 : 2.5), a top speed of Mach 2.5, and takeoff weight of 40,000 pounds maximum.

Different companies – such as McDonnell Douglas, Fairchild Republic, General Dynamics, and North American Rockwell – submitted proposals for the F-X; the final proposal stage submissions occurred in June 1969.

On December 23rd 1969, the USAF chose a McDonnell Douglas design for the F-X. The single-seated F-15A and the two-seated F-15B trainer were produced from 1972 to 1979.

The F-15A had a length of 63 feet, 9 inches, a width of 42 feet, 9.5 inches, and height of 18 feet, 5.5 inches. It had a maximum takeoff weight of 66,000 pounds, and could fly Mach 2.5 at 36,000 feet.

The F-15C – a version with an improved computer, a system for flight overload (high G-force) warnings, a higher maximum takeoff weight, a reprogrammable APG-63/APG-70 radar, and improved interior and exterior fuel capacities – was produced from 1978 to 1985. Similarly, the two-seated version of the F-15C, the F-15D was produced over the same period of time.

With the F-15C’s capacity to handle up to 9Gs, a top speed of Mach 2.5, ability to handle altitudes of up to 65,000 feet, a thrust-to-weight ratio of over 1.07, and an ability to carry various air-to-air missiles, the F-15 Eagle would perform exceptionally well in USAF use.

The F-15C would also excel in international use – with no air-to-air combat losses reported and numerous (greater than 100) air-to-air victories.

Later developments would include the F-15E Strike Eagle, a strike fighter (fighter-bomber) variant produced since 1985.

Still in service in some militaries today, the F-15 arguably has fulfilled its original intended role as an air-superiority fighter.

2. F-15s can fly twice the speed of sound.

The F-15A could fly Mach 2.5 at altitudes of 36,000 feet. This was 1,650 miles an hour, more than twice the speed of sound.

This was due to the double-engined design of the plane, carrying two Pratt & Whitney F100 (specifically the F100-PW-100) engines, with each axial turbofan engine capable of delivering 12,420 pounds of thrust (dry) or 14,670 pounds of thrust at full power. With the afterburner in action, each engine could deliver 23,830 pounds of thrust.

Strangely enough, though, Mach 2.5 wasn’t the fastest speed for a jet fighter ever – even at the time the F-15A was produced. This was by design, however, with the F-15 intended to reach air-superiority through its acceleration and greater agility over other contemporary jet fighter aircraft.

In comparison to the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II, for example, some pilots found the F-15’s propulsion system to be quite interesting. Firstly, the F-15 had two engines – something not common in many fighter jets of the time.

Also, some pilots noted the F-15 did not “bleed” off air speed – something that the F-4 Phantom II was reported to do. In speeds that mimicked the effect of multiple times the force of gravity (Gs) the Eagle would stay in fast, constant speed.

3. The F-15 can perform near-vertical takeoffs (and can climb vertically in-air).

Perhaps owing to its powerful two-engined configuration, the F-15 has the capability for vertical acceleration, a first for a U.S. jet fighter.

For example, the thrust-to-weight ratio of the F-15A – which is the comparison of the plane’s accelerative power to how heavy it is – is 1.17 : 1.

This thrust in the ratio (1.17), when compared to the weight (1), is higher than 1 : 1, which allows the airplane to accelerate in a vertical climb, even approaching near-vertical climbs shortly after takeoff.

4. The F-15 has a number of advanced flight technologies.

The F-15 Eagle is not a simple fighter plane. Technologically, it has many systems for navigation, combat, jamming, communication, landing, in-air refueling, and radar surveillance.

Some of these systems include a Pulse-Doppler radar, specifically the AN/APG-63 and AN/APG-70 radar systems. These surveillance systems use electromagnetic waves on the microwave (X band) frequency to pick up targets.

The F-15 can communicate using UHF wavelengths, has a system for all-weather (day or night) landings, and navigate with the AN/ASN-109 – and inertial guidance system – that makes use of gyroscopes and accelerometers for flight position, orientation, and velocity information.

Another advancement found in the F-15 – perhaps ubiquitous in modern-day fighter jets – is the Heads Up Display (HUD). The HUD projects light onto a transparent panel, displaying information for the pilot to see. In the case of the F-15A, the HUD was known the AVQ-20; it presented flight performance and target information.

5. Variants of the F-15 were produced for different purposes.

Different variants of the F-15 were produced since the fighter jet’s intial production in the early 1970s. The first variant produced was the F-15A, a single-seated version of the air superiority plane first flown on July 27th, 1972 out of Edwards Air Force Base, California.

The F-15B was a two-seated training variant of the F-15A. The F-15A (with 384 instances made) and the F-15B (with 61 instances made) were produced by McDonnell Douglas from 1972 to 1979.

The F-15C was an advanced air superiority version of the F-15A, with widened fuel capacities, an increased maximum takeoff weight, and with some models equipped with an AN/APG-70 (also -63(V)1) reprogrammable radar.

The F-15D was a two-seated training version of the F-15C, produced along with the F-15C from 1979 to 1985. 483 instances of the F-15C were made – along with 92 instances of the F-15D.

The F-15E Strike Eagle was a two-seated, all-weather multi-role (designed for ground-attack missions, but also air-to-air capable) fighter.

With the standard F-15’s Mach 2.5+ speeds, the F-15E has been used effectively in strike missions. From 1985 to 2001, a total of 236 instances of the F-15E have been produced.

Besides use in the USAF, variants of the F-15 have been used, or produced under contract, by countries such as South Korea, Israel, Japan, Saudi Arabia, and Singapore.