The Viper

By WavesToJets

The F-16 Fighting Falcon is a jet fighter that is light on design but heavy on function. Nicknamed the “Viper” by pilots due to its resemblance to the deadly snake, the F-16 is arguably nothing short of being just as dangerous to its targets.

This, however, is only the start of what there is to know about the F-16 – produced first for the United States Air Force (USAF) by General Dynamics, and then by the Lockheed Martin Corporation.

Here are five more facts about the F-16 Fighting Falcon.

1. The F-16 was made smaller than its contemporaries by design.

The Fighting Falcon was developed during a time when American-made jet fighters were being reduced in size. During the 1960s, the USAF and U.S. Navy had been using large, fast, heavy aircraft designed for air-to-air and ground attack roles.

A prototypical example of this type of jet fighter would be the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II. The F-4 was used primarily in the Vietnam War by the USAF, U.S. Navy, and Marines Corps. It served in air-to-air as well as air-to-ground combat, with a USAF in-air combat kill-to-loss ratio of 107.5 to 33.

At a length of 63 feet, a wingspan of 38 feet, 5 inches, and an empty weight of 30,328 pounds, the F-4 was capable of carrying over 18,000 pounds of weapons (including bombs and missiles) and a crew of two. Its General Electric J79 engines allowed the plane to reach a maximum speed of Mach 2.23.

Though this made for a large, fast, and powerful fighter, some theorists (notably Pentagon-adjacent figures like former USAF Col. John R. Boyd and mathmetician Thomas P. Christie) considered planes like the F-4 to lack the maneuverability necessary to make them effective jet fighters in air-to-air combat.

These theorists – who believed in smaller, lighter, more maneuverable fighters – were collectively, and unofficially, referred to as the “Fighter Mafia”. They based newer fighter aircraft capabilities on what became known as the “Energy-Maneuverability”, or “E-M” theory. This theory calculated in-air fighter performance based on variables of speed, thrust, drag, and weight.

By the late 1960s, jet fighters based on Boyd and Christie’s “E-M” theory were beginning to be developed. The McDonnell Douglas F-15A Eagle, for example, was developed officially starting in December 1969 and flown beginning in July 1972.

The F-15A was somewhat lighter (with an empty weight of 27,000 pounds, instead of the F-4’s 30,328 pounds) jet fighter with less capacity to carry heavy weapons – but it was more agile in flight and very capable in air-to-air fighting (the F-15 is said to have no air-to-air combat losses in its USAF service history).

But at the time of its development, even the F-15A did not live up to the theorists’ ideas of what a smaller, more dynamic jet fighter would look like. The F-15A had a length of 63 feet, 9 inches and a wingspan of 42 feet, 9.5 inches – and both of these dimensions were still longer than the F-4’s.

The late 1960s saw the the start of the USAF’s Lightweight Fighter Program, aimed at developing a jet fighter that was more in line with the vision of advocates of agile, maneuverable, lightweight fighters. In addition to the performance aspects of the proposed plane, Lightweight Fighter proponents also argued that such a fighter would be less costly to produce, and be able to be manufactured in greater numbers.

In 1971, the USAF formed the Air Force Prototype Study Group, which had “E-M” theorist John R. Boyd as a member. The Prototype Study Group had two prototypes to be funded – and a Request For Proposals (or RFP, in which the government provided the minimum specifications for a new fighter aircraft) was issued to various aviation companies on January 6th, 1972.

The specifications issued included that the new fighter be able to fly in combat ideally at 30,000 to 40,000 feet, weigh 20,000 pounds, have a optimal combat speed of Mach 0.6 to 1.6, a long range, adequate acceleration, and enough agility to turn quickly in flight.

Northrop, Lockheed, Boeing, General Dynamics, and Vought all sent proposals. General Dynamics was selected to create what would become the YF-16, the prototype of the F-16 Fighting Falcon (in the same program, Northrop was chosen to develop the YF-17, what would become the F/A-18 Hornet).

The YF-16 would fly officially for the first time on February 2nd, 1974. Shortly after, the USAF selected the prototype as the basis for the F-16 Fighting Falcon.

There were to be two versions of the F-16 made for USAF use, at least initially. The F-16A would be a single-seated fighter, while the F-16B would be a two-seated trainer.

Before any of the USAF planes were produced, there were alterations to the YF-16 made – including an expanded nose cone for an AN/APG-66 radar, a longer fuselage (by 10.6 inches), and modifications to the wheel bay doors, dorsal, and ventral fins.

The F-16A was first flown on December 8th 1976; the F-16B was first flown on August 8th, 1977. The plane was designated the “Fighting Falcon” on July 21st 1980 and was used in the USAF starting on October 1st, 1980.

The F-16A was equipped with a 12,240 pound-thrust (dry) Pratt & Whitney F100-PW-200 turbofan engine. It had a maximum dry (AKA military) thrust capability of 14,670 pounds – and with the afterburner on, had a thrust of 23,830 pounds.

The F-16A also was 49 feet, 3.5 inches in length, had a wingspan of 32 feet, 9.5 inches, and an empty weight 16,285 pounds (25,281 pounds with a combat load). At an altitude of 40,000 feet it could reach a top speed of Mach 2.05 (1,573 miles per hour).

The range of the F-16A was 2400 miles; it could accommodate two 370-gallon external fuel tanks on the wings and one 300-gallon fuel tank underneath the fuselage. The plane was equipped with a 20-mm inset cannon (next to the canopy) and had hard points on the wings (and wingtips) for air-to-air missiles.

Later versions of the F-16 (like the single-seat F-16C and two-seated F-16D) would improve upon range, thrust power (to some extent), and the ordnance-carrying capabilities.

When compared to the then-recently produced F-15 Eagle, the Fighting Falcon was smaller, lighter, and with the F-15’s maximum speed at Mach 2.5 – indeed, a little slower.

But the F-16 was certainly more maneuverable, and was noted for its excellent turning capabilities and agility in-air – and this was in-combat performance created for the F-16 Fighting Falcon by design.

2. The F-16 operated with advancements in its flight control system.

The F-16 Fighting Falcon was designed with several pilot-friendly features. Some of these features included a near-unobstructed bubble canopy (which, except for the linking back frame, allowed the pilot to have increased forward, upward, side, and rear vision), a seat that tilted 30 degrees back (instead of the conventional 13 degrees, for higher G-tolerance), and a side-mounted control stick (rather than the traditionally-oriented center-mounted stick for fighters), which was intended to help pilots operate under substantial G-forces.

These features, however, could possibly be considered secondary improvements in comparison to the F-16’s flight control system. The Fighting Falcon was made by design to be slightly unstable in flight, allowing for what is referred to as relaxed static (or negative) stability.

In conventionally-designed airplanes before the F-16, planes had a tendency to become sporadically unstable (make small shifts in pitch, roll, and yaw) so long as the pilot held the controls. This was usually corrected once the pilot released the controls temporarily, allowing the plane to straighten out in flight. This “straightening out” is known as positive static stability.

The F-16 was designed to have negative static stability – which meant its control was made unstable on purpose to increase its maneuverability. Also known as relaxed static stability, this was to make the Falcon more dynamic in scenarios such as air-to-air combat.

This instability, however, had to be corrected by a flight control computer and a hydraulics system to shift the ailerons in the tail and the wings. This was to keep the plane from going completely out of control in flight.

The F-16’s flight control computer adjusted the physical configurations of the plane through constant calculations – to maintain the stability that would normally be achieved through a conventional plane’s positive static stability.

As the F-16 approached reached velocities above speed of sound, however, the familiar aspects of positive static stability did come back into effect.

The flight control computer and hydraulics were further assisted by a fly-by-wire (FBW) system – a system that converts a pilot’s adjustments on the flight controls into an electronic signal. The signal then gets transferred to the flight control computer via a wire.

The flight control computer receives this signal, then makes adjustments to the plane’s physical exterior control surfaces (the rudder, ailerons, etc.) in accordance to what it regards to be the pilot’s originally desired outcome – for the intended changes in pitch, roll, yaw, and directional velocity.

Though the FBW system was not exactly a new aircraft control development, the F-16 was the first U.S. production aircraft to use a digital FBW system. This, the flight control computer, and the F-16’s hydraulics demonstrated advancements in flight control systems at the time, especially for fighter planes.

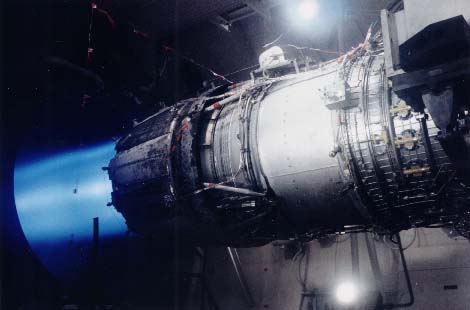

3. The F-16 uses two different engines.

When it was first developed, the F-16 Fighting Falcon used the Pratt & Whitney F100-PW-200 engine, a unit with a maximum output of 23,830 pounds of thrust.

Since the PW-200 had performance issues, later F-16s used the 23,770 pound-thrust (max) F100-PW-220 engine. This engine could be controlled digitally through electronics, thus reducing reducing the chance of stalling. Earlier -200 engines could be upgraded to -220 specifications; they would be known as -220E (equivalent) engines.

By the mid-1980s, the F-16’s engine costs had become an issue for the USAF. The USAF’s answer to this was the Alternate Fighter Engine (AFE) program, a competitive contract program for engine production.

As a result of this program, General Electric was selected to provide engines in addition to Pratt & Whitney. General Electric’s F110-GE-100 turbofan engine, when equipped to an F-16 with an enlarged inlet duct, could reach a 28,984 pound-thrust (max) output.

Since the F-16 was produced in groups known as blocks, the “0”-ending blocks would contain General Electric engines and GE-specific inlet ducts, while “2”-ending blocks would be fitted with Pratt & Whitney engines.

In the early 1990s, a further USAF engine development project, the Increased Performance Engine (IPE) program, saw marked improvements to both the Pratt & Whitney and General Electric engines.

The F100-PW-229 was the improved Pratt & Whitney engine of the IPE program. The PW-229 was a 29,160 pound-thrust (max) unit, used for the F-16 Fighting Falcon – and incidentally, also for the F-15E Strike Eagle.

The F110-GE-129 was the IPE’s improved General Electric engine. With increases of high-altitude and low-altitude thrusts of 10 percent and 30 percent respectively, the GE-129 had a maximum thrusting force of 29,588 pounds.

F-16s starting at Block 50 and above would be built with either improved GE or Pratt & Whitney engine. Out of 1,446 F-16 Cs and F-16Ds produced, 556 would use the Pratt &Whitney PW-229 and 890 would use the General Electric GE-129.

Depending on the plane, the latter F-16s (C and D versions) do indeed use two different engines – but can still reach speeds of Mach 1.2 at sea level and Mach 2.05 at 40,000 feet.

4. The F-16 has been built and used worldwide.

The F-16 Fighting Falcon was originally produced in the mid-1970s in the United States. General Dynamics first manufactured the plane, and since 1993, the Lockheed Corporation (now Lockheed Martin) has been the primary manufacturer.

But this is only part of the F-16’s story, as production has taken place in several other countries. Starting in the late 1970s, the F-16, and some of its component parts, have been produced in Europe.

These countries include Belgium, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, which have in whole (also in part) produced F-16s.

The air forces of these countries have used the F-16 as well; the F-16 has also been produced under license in countries such as Turkey and South Korea. In Japan, an F-16 derivative was developed as the Mitsubishi F-2.

The F-16 Fighting Falcon has also been used in the air forces of Israel, Jordan, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan, Indonesia, Chile, and several other countries.

It has not been uncommon for these countries to upgrade the F-16 with up-to-date features (such as radar, avionics systems, and computer improvements) and/or adjustments (such as canopy or fuel tank changes) for regional use.

5. The F-16 is not just an air superiority fighter.

Though the F-16 Fighting Falcon was designed to be an extremely maneuverable and capable air-to-air fighter in order to achieve the goal of air superiority over a given area, it has been developed for other purposes as well.

One of these developments – although only a proposed purpose – was close air support. General Dynamics developed a variant containing a greater number of cannons and heavy-duty wings, to be called the A-16. This variant, however, did not see past the development stages of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

An F-16 purpose that did come to actualization was reconnaissance, with different variants equipped with Low Altitude Navigation and Targeting Infrared at Night (LANTIRN) pods.

These exterior pods have cameras that map infrared images of the surrounding environment – which in turn are put on the Heads Up Display (HUD) to help the fighter navigate at low altitudes through all-weather conditions.

The F-16A/Bs of Block 20 and F-16 D/Es of Block 40 have used LANTIRN pods at least since the 1990s, equipped with a Martin Marietta (Lockheed Martin) technology in USAF use since 1987.

With its Mach 2 flying ability, its capacity for relaxed static stability, 20-mm cannon, advanced radar/navigation, and multiple hardpoints for missiles and bombs, the F-16 Fighting Falcon has indeed proven its abilities in combat, perhaps for many years to come.